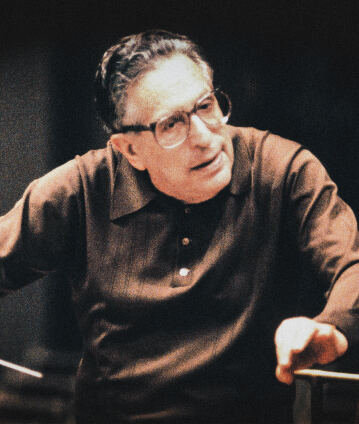

Kurt Sanderling conducts Tchaikovsky and Saint-Saëns

Kurt Sanderling was one of a group of legendary conductors that included Sergiu Celibidache, Georg Solti and Günter Wand, all of whom were born in 1912. For the present concert with the Berliner Philharmoniker in 1992, he chose two 19th-century masterpieces: Saint-Saëns’s Second Piano Concerto, in which the brilliant soloist was the young Yefim Bronfman, and Tchaikovsky’s impassioned Symphony No. 4, one of Sanderling’s calling cards.

Kurt Sanderling was the last surviving member of a generation of conductors whose roots lay in Romanticism but which continued to be active until well into the 20th century, in that way forming a bridge between the two periods. He had only made his debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker four years before the concert documented here – at the age of 78. Sanderling began his career without any formal training as a répétiteur at the Städtische Oper in Berlin, before emigrating to the Soviet Union in 1936 and becoming the Leningrad Philharmonic’s assistant principal conductor under Evgeny Mravinsky from 1942 to 1960 and evolving into one of the 20th century’s leading conductors. In 1956 he made what continues to be regarded as a legendary recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony with the Leningrad Philharmonic. In the view of the Washington Post, he had a very special affinity with this music: “Sanderling’s Tchaikovsky is filled with an unselfconscious dignity that never gets in the way of the music’s dramatic flow but keeps the musical and emotional elements in proper balance. There is no trace of self-indulgence or whim in his approach, no hotting-up, just great respect for the score and for Tchaikovsky’s own good judgment.”

In the first half of the concert listeners were bowled over by Yefim Bronfman’s contribution to Saint-Saëns’s Second Piano Concerto, a work that was written in eighteen days for the conducting debut of his friend Anton Rubinstein in Paris in 1868. It is one of the rare examples of a piano concerto in which the solo instrument opens the musical argument. Equally unusual is the fact that the slow movement is in first position, initially creating the impression of a Baroque prelude. This is followed by a witty Scherzo and a lively Tarantella that Bronfman mastered with bravura aplomb, while at the same time making it unmistakably clear why this concerto is one of Saint-Saëns’s most popular works.

© 1992 EuroArts Music International

Artists

Our recommendations

- Tugan Sokhiev and Yefim Bronfman perform Beethoven

- Yannick Nézet-Séguin makes his debut with Berlioz and Prokofiev

- Herbert Blomstedt and Yefim Bronfman

- Simon Rattle conducts “Russian rhythms” at the Waldbühne

- Daniel Barenboim and Yefim Bronfman perform Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1

- Zubin Mehta and Yefim Bronfman